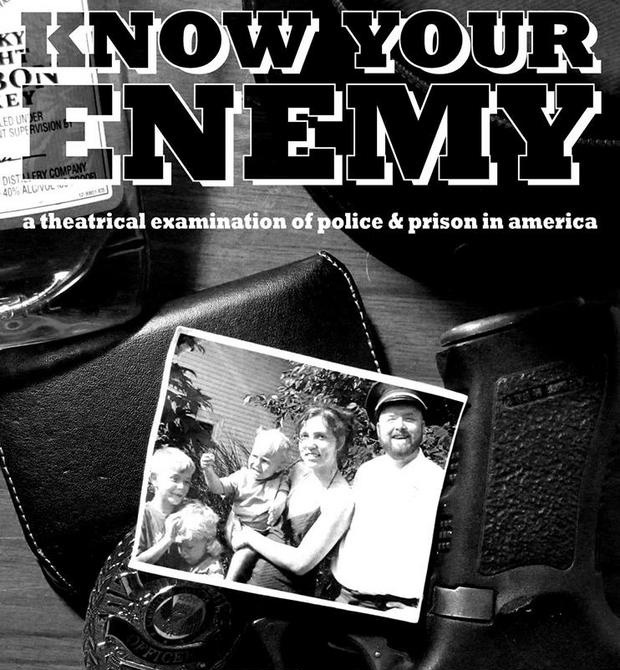

Guide to Kulchur, a cooperatively owned and run bookstore in Cleveland, Ohio with anarchist affiliations, attracted me when I first found it on the Internet. Of course, when I read they were hosting a play called “Behind the Badge,” described as a “theatrical examination of police and prison in America,” I knew I was going.

The play is produced by Insurgent Theatre, which member Ben Turk, 35, described as a radical, Do-It-Yourself (DIY) theater company. The company was formed in Milwaukee, Wisconsin in 2003. Originally a local company, it began to tour the nation in 2008.

“Behind the Badge” was written by and performed by Turk.

The first thing I noticed about Turk was that he was barefoot. The second thing I noticed was that he was carrying a box, and the third thing I noticed was that inside this box were the contents of his soon-to-be set and soon-to-be costume.

Astute observational skills one can only pick up in journalism school.

My next observation was a political one, perhaps too political, but I was in the basement of a co-op that hosted Cleveland’s most recent Anarchist Book Fair and was in the presence of a man from a group called Insurgent Theatre, so I figured it was on the table.

What I noticed was that the few people who had trickled in at this point asked Turk as he set up, do you need any help? He accepted their help, and I couldn’t help but feel a certain collectivist ethos, a feeling of solidarity and equality in the fact that the audience was helping set up what they would soon be watching.

And participating in.

Eventually, the personable, barefoot man got into costume and became the temperamental, booted police officer radical leftists love to hate, and for the show, he asked for a volunteer from the now 20-strong audience.

The volunteer would play a detained prisoner, bearing both an orange jumpsuit and handcuffs during the play and would have to be silent, straight-faced and staring at Turk as he spoke to and oftentimes screamed at the prisoner.

“Behind the Badge” was essentially a monologue performed by Turk who played a police officer believing himself to be a good cop: one who fights within the system to truly make the lives of citizens safer and better.

Throughout the play, the officer constantly attempts to establish a relationship with the prisoner, but the prisoner never speaks or responds, and this resistance forces Turk to become defensive. Although the prisoner doesn’t vocalize any arguments as to why there is no such thing as a good police officer, Turk does, attacks these arguments at first, but eventually concedes to them.

The police officer eventually exclaims, “I am a slave catcher,” and “Abolish prisons; free all prisoners!”

These statements arise after reasoning that the police officer is necessarily part of a state-capitalist system which demands him to uphold its policies, and these policies are, according to Turk, containment and detainment of the poor. The problem isn’t evil cops—the officer in this particular play considers himself to be a family man with good intentions—the problem is that police officers fulfill the state’s need to repress the poor and protect concentrated wealth.

In addition to this systemic role, Turk explained his opinion that police serve another function for the rich.

“It goes to the point where their humanity is threatened by seeing a homeless person or seeing a sex worker or seeing anybody who is living in desperation while they live in luxury,” Turk said. “So the law not only protects their private property, it also protects their worldview and their ideology and their self-perception as good people despite the massive wealth gap.”

During the play, the officer acknowledges facts such as “grounds maintenance worker” is a more dangerous occupation than “police officer,” which make him question both his job’s worth and the type of person he was actually locking away. Perhaps these were not good-for-nothing, bad-to-the-core criminals, but disadvantaged human beings whose poverty predisposes them to crime.

Not only that, but Turk said their inability to afford a lawyer leads to having appointed state defenders who strongly advise them to plead guilty even if they did not commit the crime, thrusting them into a prison system full of torture.

Yes, torture—not medieval-type torture because that would leave physical scars and would probably not be tolerated by the public—mental and emotional torture such as solitary confinement, constant humiliation and dehumanization through means such as sensory deprivation and other forms of violence such as using pepper spray.

According to Turk, due to a large number of prisoner uprisings in the 1970s, 80s and 90s, the United States was faced with a decision of either eradicating the prison system in favor of something more economically sustainable or committing to prisons and incorporating torture and other methods of control in order to prevent riots.

“Without all these systems of control,” Turk said, “prisoners would get organized. They would push back; they would tear the prisons down from the inside-out. They were doing it before we brought those things about.”

Throughout the play, Turk would pause the performance and facilitate a discussion with the audience, asking them to list components of the criminal-justice system, forms of torture and other items related to the play, and he would write these answers down and hang them on the wall behind him.

After each discussion, he would rearrange chairs on-set, giving the audience a different perspective of the room each time. Offering a different view of the room as well as the interactivity with the audience are results of Turk’s theater mentality.

“I think that theater should focus on what theater can do that other art mediums can’t do,” Turk said. “People talk about theater being a dying art because movies, television, YouTube are supplanting it in some kind of way, and a lot of people making those complaints are doing plays that could just be movies instead—that are seen from one angle, that don’t interact with the audience.”

Engaging one’s audience both conveys a message and empowers the individuals participating, which should be the goal of any political education, whether the target audience is full of radicals, mainstream Americans or apathetic citizens. Regarding Turk’s audience on any given day, he said he is realistic about his goals.

“I recognize that people aren’t going to go out to a DIY theatre event called Insurgent Theatre in the basement of a bookstore in Cleveland unless they’re already somewhat left-leaning, radical, anarchist, whatever,” Turk said. “So I hope that the play goes beyond just ‘fuck the police,’ beyond just, ‘all cops are bastards,’ fleshes that out and looks at it more closely, challenges it in some ways, but also reinforces and deepens the analysis that we bring to policing and these things that we all know that we oppose, but I want us to have a more sophisticated opposition to it.”

Nuance and critical analysis is healthy for anyone’s political views, and this sort of dissection does not mean the passion that is often associated with those who yell slogans such as “fuck the police” will be dimmed—it will just stand on stronger ground.

As for Turk, he is channeling his passion into a demanding tour and a new project called SupportPrisonerResistance.net, which he described as an amassing of resources and strategies to, well, support prisoner resistance.

Education, agitation, participation, empowerment and solidarity: through these ideals, Turk believes prisons can eventually be abolished.

To see if a production of “Behind the Badge” is coming to your area, click here.

Donate to Insurgent Theater here.